Bloomsbury is putting out an Indian Version of Bending Genre.

That is all.

Miss you!

Nicole

Bloomsbury is putting out an Indian Version of Bending Genre.

That is all.

Miss you!

Nicole

Part I

I am an essayist. Ever since I started keeping a journal when I was eighteen, I’ve thought in essay, in narrative, in truth. My life is offered back to me in the mirror of creative nonfiction, in finding metaphor and art in life and fact.

*

Since that first river heartbreak:

Those late nights, when stars are the only

friends, I floated beneath

the surface of water.

The peace of silence.

Since then:

a poet.

*

I relapse into fiction once or twice a year (maybe like those younger-day mistakes I used to make during late nights when I drank too much and chased after the shadow of the moon).

When someone tells me a story and I think, I need to let that story wander where it may. And I will follow along. During those short windows, I explore invention, fiction.

*

The art of the empty stage: drama. A genre I’ve never studied. But the camera is so close, intimate, like falling in love, that first night. The hardest kiss. Or the night of the breakup. Nights alone.

Though I don’t know drama, I understand the feeling aloneness on a stage, a hot beam illuminating our essential aloneness.

*

Part II

I teach an intro level, multi-genre creative writing class at a small Vermont university. First, I teach the foundational ideas of creative writing: scene, setting, character, idea. Only then do I teach the four genres.

*

Definition: Genre is a category of writing based on shape. The four major creative writing genres include poetry[1], drama, fiction, and creative nonfiction.

*

Title: The Teaching of Genre in a One Act Play.

Setting: A stage filled with twenty desks and twenty students. A professor, bald, 40ish, thin, walks across the stage.

Teacher: “Genre is a way to categorize writing based on its shape.”

Students nod their heads.

Teacher: “Creative writing has four genres. Can anyone tell me what they are?”

Smart Student: “Fiction …? Poetry?”

Professor nods his head.

Other Smart Student: “Drama?”

Smartest Student: “Oh, and real stuff.”

Teacher: “Yup, creative nonfiction.”

Classroom is filled with smiling, happy students and proud professor.

Smart Student: “How are the shapes of fiction and nonfiction different?”

Teacher: “Err. Some genres are based on shapes, like poetry and drama. But some deal with whether they deal with truth or fiction.”

Smarter Student: “So genre is either shape or truth/lack of truth?”

Students look confused.

Teacher wrings his hands.

Teacher: “Okay, let’s start over. We have prose, poetry, and playwriting. Those are our three shapes of writing. These are the shapes a piece can take on the page. Prose is any writing done in paragraphs. Poetry is any writing done using line breaks. Drama uses playwriting techniques.”

Students smile again.

Smart Student: “Wait, are poetry and drama true or invented?”

Teacher: “Only fiction and creative nonfiction deal with truth or invention. Poetry and drama just deal with shape.”

Smartest Student: “Why?”

Teacher paces in front of classroom.

*

Is this confusion between truth and shape within genre merely a problem for the random professor? Merely an issue in the classroom? No. For this writer, there are a plethora of problems with our current system of how genre seems to use both shape and truth as its defining characteristics, that tries to meld together these differing ideas on what genre is, that offer only false borders.

As a writer, I am stuck trying to explain my writing to editors, agents, readers, and publishers.

I write micro-essays that look like poems. What do we call that?

Creative nonfiction poetry?

Prose poems?

Lyric essays?

How will the reader know that these poem-like things are truths? How will they understand that truth is the heart of these pieces and the shape serves the truth I am trying to get at?

My friend, Julia, calls these hybrid pieces that span shapes Thingamabobs, which just highlights the problem. Julia and I, and so many other writers, are forced to create unclear terms to try to define something that should be easily defined. We are writers. We work with language. How is it that we have no language here?

And then there is the issue of bookstores. I read environmental and nature writing. When I go into a bookstore and search for nature writers, I look in the Nature Writing section. Easy enough. Unless I want environmental poetry. Then I need to go into the Poetry section. Here, I’ll find nature poets like David Budbill and T’ao Ch’ien kissing covers with lyric poets like Ezra Pound and ultra-talk poets like Mark Halliday and confessional poets like Sylvia Plath. These poets are lumped together for their reliance on line breaks, on their shape. This organizational system of gathering likeminded things together might tell us to call a house and a cardboard box the same thing since they share the same rectangular shape.

Also, the reader often has an unclear understanding of what they will be receiving from the writer. Is that poem true, invented, or something else?[2] What is the small paragraphy-thing? A prose poem? A lyric essay? What is the difference? We can be more clear with the reader. We can tell them exactly what they will be holding in their hands. Genre, or shape, is normally easy for a reader to see just by examining a piece of writing. Most poems clearly use line breaks. Most fiction and creative nonfiction clearly use paragraphs. But truth/fiction is not something that can be seen. It can only be told to the reader. Once the reader knows what they are reading (genre and truth/invention), then they can decide on how to use that information or if that information is even important. But right now we often don’t provide that information to the reader.

Finally, as writers, we have been taught to write truth or fiction in prose, to often ignore truth or fiction in poetry and drama, and to see creative nonfiction as only prose. These are artificial limitations. These constraints hem us in for no reason. A poem can be true. Creative nonfiction can use playwriting techniques. Fiction can use historical information and fact. Drama can be true or invented.

*

Etymology of Prose: Prose is birthed from the Latin word for straightforward. Prose uses paragraphs, sentences, and traditional uses of punctuation.

Etymology of Poetry: Originated from the Latin word for poet, poetry originally meant maker or author or poet.

Etymology of Drama: Drama comes from the Greek words for to act, to perform, to do.

Etymology of Genre: Originates from the French word for kind, sort, style.

Part III

What is genre?

We saw the definition and etymology above, but let’s start here. We have four genres:

That’s pretty simple.

Before we visit with genre, let’s examine how the use of (or lack of) truth affects pieces. Maybe truth will offer clarifying ideas. Here’s a simple chart looking at truth in our genres.

| Truth/Invention in Our Genres | Truth/Invention |

| Creative Nonfiction | Truth |

| Fiction | Invention |

| Poetry | Unclear |

| Drama | Unclear |

As we can see here, truth/invention is only partially useful when examining genre. Truth/invention works great with creative nonfiction and fiction but doesn’t work at all for poetry and drama. So truth doesn’t clarify enough for us. It leads to more confusion.

Next, let’s examine the keys to figuring out what makes a genre a genre.

| Genre | What Makes It a Genre? |

| CNF | Truth + Paragraphs |

| Fiction | Invention + Paragraphs |

| Poetry | Line Breaks |

| Drama | Playwriting Style |

Though this chart is simple, it’s also confusing.

Two of our genres deal with truth or lack of truth (fiction and creative nonfiction) plus shape (paragraphs).

Two deal with shape (line breaks or playwriting).

So we are no farther along. Genre is unclear (because two of the genres focus on truth and two focus on shape) and truth is ineffective because two of the genres don’t care about truth.

*

Title: The Teaching of Genre and Shape Overlapping, a Two Act Play (Act I)

Setting: a stage empty expect for twenty desks filled with twenty students. A professor, bald, 40ish, thin, stands at the board looking at his diagram, which he has labeled “Illustration of Genre and Shape Overlapping.”

Teacher: Points to illustration. Looks confused. Tries to explain how genre and form works. Sputters. Erases work.

*

Thesis:

What if I want to write creative nonfiction in poetry form?

What do we call that? Essay? Memoir? Poem?

If we call it essay, we wonder about shape.

If we call it poem, we wonder about truth (or lack of truth).

I could go on and on.

[See confusing illustration above.]

*

Part IV

We need to move to a system that offers rational borders and removes the false limitations that have been set on our genres. What is the solution to this overlapping confusion of genre and shape?

Let genre teach us only the shape of a piece since the term genre originated to mean style and never was meant to include fiction or truth. Maybe this problem originated with the invention of the term “the fourth genre” for creative nonfiction. Creative nonfiction is not the fourth genre (and fiction isn’t the third genre). Rather, prose is the third genre but before creative nonfiction became popular, fiction was seen to equal prose. Now we see fiction and creative nonfiction as genres rather than as types of prose.

Once we have moved to three genres (poetry, drama, prose), then let us create a new category that deals with truth or invention. I propose veracity.

Definition of Veracity: The observance of truth, or truthfulness, of a thing, something that conforms to truth and fact.

Etymology of Veracity: From Latin, meaning truthful.

So we will have two (or three) veracities. Veracity only teaches us about the truthfulness or invention of a piece.

| Veracity | What Makes a Veracity |

| Creative Nonfiction | Truth |

| Fiction | Fiction |

| Hybrid[3] | Inhabits truth and fiction |

And let us have three (or four) genres. Genres will only teach us how a piece will look on the page.

| Genre | What Makes a Form? |

| Prose | Paragraph Form |

| Poetry | Line Break Form |

| Playwriting | Playwriting Form |

| Hybrid | Multiple Forms |

*

Dichotomous Key to Veracities:

Nonfiction:

Habitat: Lives in areas of sunlight populated by truths, facts, memories, and speculations.

Location: Can be found in prose, poetry, and drama.

Appearance: Carries the appearance of the writer’s life or the life of those who the writer has studied.

Times: When the writer wants to examine the factual, the truth, the real in a moment.

Fiction:

Habitat: Lives in caves populated by invention.

Location: Can be found in prose, poetry, and drama.

Appearance: A changeling. Can appear like the writer, like other humans, or entirely unlike humans at all.

Times: When the writer wants to create something new, when the writer longs to invent.

*

Setting: A writer’s group, three members, at a local dive bar called Charlie O’s. Practicing a new way to view genre and veracity.

Jess: So what would you call Anne Carson’s The Glass Essay?

Jess and Julia in unison: “Hybrid/hybrid.”

Julia: “What about Moby Dick? It’s fiction and nonfiction and it is prose.”[4]

Jess: “Catcher in the Rye is fiction and prose.”

Jess: “Jeanette Walls’ The Glass Castle? Nonfiction/Prose.”

Sean: “The ancient Chinese poets, like T’ao Ch’ien? Creative nonfiction and poetry.”

Jess: “In Cold Blood?”[5]

*

What does this new system allow that sees genre as poetry, drama, and prose? That offers a scale for veracity of a piece?

One: It makes the teaching life easier. This simpler view on genre and veracity is easy to teach. Every piece of writing is:

We can go back to calling a cardboard box a box and a house a house.

Two: It allows writers flexibility to conceive of how they should write on the page. Writers may no longer need to feel constrained by genre and veracity because we’ve separated truth and fiction from genre.

Choose a genre(s).

Choose a veracity(s).

Write.

Three: This system allows publishers a way to clearly articulate what they want. Again, just choose a genre(s) and a veracity(s) and the writer will know what to submit.

Four: This new system instructs the reader more clearly on what they will receive. The contract is clear between writer and reader. Veracity teaches us about truth/invention. Genre teaches us about shape.

*

I am an essayist. But I see my truths, attempts, tries at understanding life not always in the long paragraphs of prose. Sometimes my brain, heart, hands need, yes, other forms.

To tell

my truths through poetry.

I don’t want

to be

constrained by form.

Let my words, like the waters

of my life, wander.

[1] There exist hundreds of definitions for poetry. Most offer major flaws in how they categorize poetry. The only definition I have found that doesn’t have major holes (because of its simplicity) is that poetry, almost always, uses line breaks to determine the shape of the poem. Except when it’s called ‘prose poetry.’ And once again, the professor looks confused.

[2] My friend Karen just said that she reads most poems as “real” or “based on the writer’s life.” I read most poems as invented by the writer. We, the reader, have no idea if a poem is real or invented.

[3] Hybrid texts intentionally blend fiction and nonfiction, play with fiction and nonfiction, or have fiction and nonfiction share space. We can continue to work to decide where the hybrid boundary begins and ends, but it seems that the hybrid space could be reserved for pieces that mix or play with truth and fiction.

[4] We decide on fiction and prose because the heart of the novel is about the invented story not the nonfiction on whaling.

[5] We’d still need to work out some kinks (like where to place In Cold Blood), but the kinks are smaller and on the edges of the borders. So rather than dealing with major issues in how our genres and shapes overall and confuse, we’d have to deal with smaller borderland issues like Is IN Cold Blood nonfiction or hybrid.

Sean Prentiss is the author of the memoir, Finding Abbey: a Search for Edward Abbey and His Hidden Desert Grave. Prentiss is also the co-editor of The Far Edges of the Fourth Genre: Explorations in Creative Nonfiction, a creative nonfiction craft anthology. He lives on a small lake in northern Vermont and serves as an assistant professor at Norwich University.

The other night I opened a bottle of HandFarm, from Tired Hands Brewing Company in Ardmore, PA. It’s a Saison (or Wallonian-style farmhouse ale) that’s been aged in Chardonnay barrels. The base farmhouse ale is tasty enough: chewy grain flavors spiked with flavors of minerality, lemon juice, white pepper (not from the use of actual lemon or pepper; those flavors are some of the thousands of possible flavors created during fermentation). But the time spent in used oak gives it additional notes of vanilla and a slight woodsy astringency. In the barrels the mixed fermentation cultures – brewer’s yeast isolated from rural southern Belgium as well as native microflora & bacteria from Pennslyvania – flourish and multiply, lending a kumquat-like lactic sourness, and a funk that calls to mind horse stables — their smells of sweaty manes, manure, and old hay.

***

This is an essay on craft and, rest assured, I do not make drinking part of my process. I’m bringing up alcohol to illustrate a point. While enjoying this farmhouse ale, the sun waving goodbye over rowhome rooftops in South Philly, I began to think about writing in terms of beer. The initial metaphor I was teasing out between sips was that bottling a beer is like publishing an essay. Your thoughts brew and brew over the course of drafting and, of course, you want to end up with your sharpest, most finely crafted version, so you stop drafting at some point, stop thinking. You have a sense of when the essay is as good as it will be, knowing that you can overdraft a piece, can overthink the subject and let slack the tension. You bottle it for distribution when it’s at its peak. HandFarm, however is a bottle conditioned beer, meaning that the yeast is active in the bottle. The beer, quite purposefully, continues to develop in ways commensurate with variables of time and storage. Just as I’m sure you’ve noticed how essays from James Baldwin or Eula Biss have only gained potency with time. Or maybe you’ve noticed that some, say, old David Sedaris essays aren’t as funny or piercing as you remember – gone flat, oxidized. Our relationship to our essayed thoughts, as well as any reader’s relationship to our thoughts & their own thoughts, and everyone’s relationship to the world at large, is quite active. Digesting the sugars around us. Boozing up the place.

***

“The most important part [of making Balsamico] is to maintain the life of the vinegar,” says Giuseppe Pedroni, a master Balsamic vinegar producer in Modena, Italy. For him there is no growth or progress, no final product, without the preservation of that initial spark. The first vinegar must inform all others.

***

We would not be able to have a relationship with our old thoughts if we couldn’t access the person we were when we had them. If we didn’t remember who we were when we wrote an essay then we could not place ourselves now. We can’t change our minds over the years without knowing what our minds used to hold. This epistemology is holding up an idea I’m trying to access in this essay, which is that retaining an intimacy with the self’s past, any and all past selves, is necessary to age beautifully. While it may be close to impossible to control how any one essay holds up to you or the world it thinks about, you do have more control on how to hold up as an essayist.

For this I return you to HandFarm. This bottle is from the 5th batch of HandFarm, with each new bottling more complex & integrated than the last. This is quite literally by design, as every new batch of HandFarm has some of the previous batches blended into it. This is not like baking bread, where each new loaf is puffed up by literally the same yeast, a mother yeast. HandFarm would be more like if each new loaf of bread contained within it an actual hunk of an old loaf of bread, which itself enveloped an even older piece of bread, and on and on down the line. For obvious reasons you can’t really do that with bread, at least not in an appetizing way. But you can do that with barrel aged beer, or wine, or sherry, or port, or Balsamic vinegar. This process is most commonly called the Solera method. Liquidity hybridizes the old and the new. A fluid becoming. No seams or stitches.

***

Most Solera processes involve removing half of an old barrel’s contents to bottle, refilling the barrel with fresh liquid, then doing it again when next they bottle. Sometimes you remove half from the first & largest barrel only to place that siphoned liquid in a second, smaller barrel to age further. Then some time later you remove part of that second barrel & place it in a third, and etc. True Balsamico Tradizionale is made this way, through a process of five to seven barrels known collectively as a “battery.” A fresh battery of barrels is started for major life events, like a wedding or childbirth, and the first bottling from that battery won’t happen for a minimum of twelve years.

According to beer writer and technologist Lars Marius Garshol, it would take about 184 years before the last remaining molecule of the Balsamic vinegar that started a Solera is emptied out, if we define “completely emptied” as some molecular biologists and mathematicians do as “one five octillionth of the original.” Zeno, I’m sure, would regard the Solera method as paradoxical.

***

Time in the barrel will change a thing. I like to over draft my ideas at first and then give a considerable amount of time before I revise them. That’s what works for me. I enjoy seeing how far my thinking has come in the weeks between. I like to feel the influence of new perspectives & experiences tugging on the old text. I tend to prefer the speakers of my essays be “a version of me from a general time in my life” rather than “a version of me on one specific day.”

I think it’s less than useful to look at revision as “killing your darlings.” Even in the act of pressing the delete key I don’t think of it as a killing, a reaping. I think of it as vaporization. I think of it as the Angel’s Share: the phenomenon where some of the water volume of liquid aging in a barrel will evaporate, leaving the barrel filled with something more concentrated, more potent, than before.

***

Solera, in Spanish, means “on the ground,” referring to where sherry barrels were quite naturally kept before artisans started experimenting with subterranean and lofted storage. In English, we have plenty of clichés and idioms about the ground. Keeps me grounded; on the ground floor; common ground; break new ground; cut the ground out from under my feet; lose ground; hold your ground; gain some ground; I’m just run down to the ground; old stomping ground; doesn’t know his head from a hole in the ground; what moral ground do you have. There’s a sense of commonality with the word. We share it, even when we frame it antagonistically (lose/hold/gain). It unites us. Everyone walks upon it. Everyone recognizes it as the starting point – ground level. So if you think of your essays, your body of work as an essayist, as functionally a Solera method, then the process makes sense. We can’t not ground our essays. Our essays can’t help but walk the land they share with each other.

***

Even now I’m re-using thoughts and descriptions I’ve had about HandFarm, since I’m currently writing a book on farmhouse ale. It’s partly a memoir of my family’s farming history as a way to access why I love farmhouse ale so much and partly a more journalistic look into why farmhouse ale is sharply rising in popularity in the United States and I’m not saying any of this as a plug to prospective agents (though my email is in my contributor note!) but rather to demonstrate that this beer is working its way into many of my seemingly disparate thoughts, and that’s not a mistake to let the subject of my book project creep into other things I’m working on. The realization I’m having here is that it’s entirely natural.

I try to write about my grandparents escaping a hardscrabble agrarian life and along the way this beer, or another like it, shows up in my essaying, creating tension, trying to smooth away the cracked-earth of a droughtstruck farm with its gestures towards the beauty and romance of the pastoral. I try to write about the craft of essay writing using this beer merely as a way in but it fights me for the focus.

And this is nothing to shy away from or edit out. This is epistemological. This is how we stay connected to our thoughts, how none of our essays are truly written in a vacuum. Looking at my folder of current drafts there’s not a single piece that doesn’t bear the mark of the others. There’s the interviews I did at Boulevard Brewing Company for this Saison book, looking out on the brewery’s big roof towards fields of corn and soy north of Kansas City. There’s the Missouri pastoral coming up in a different essay as evidence of privilege and as contrast for citizen outrage over police fascism across the state in Ferguson. There’s the emotionally draining late nights spent watching livestreams of Ferguson juxtaposed with the elation of the World Series run for my Kansas City Royals in another. There’s the last baseball games my grandfather would see before he passed away, and there’s the news around the time of his passing that my mother got diagnosed with cancer, and there’s the weeks I spent this past semester in something like depression, and there’s the first draft I wrote after weeks of not writing — wherein a jean jacket I bought reminded me of Roger, a poet/teacher/friend, who passed away a few years ago & the memory that Roger introduced me to craft beer in the first place.

***

This is a Solera. Somewhere in every essay I write, yours too, is a bit of the previous blended in, which itself had some of the one prior to it, which in turn implies a whole cosmology for every essay. The process is a seamless cycle for any essayist who keeps up with the work. Just because we finish an essay doesn’t mean those thoughts & the emotions they kicked up don’t get blended back in with the next barrel. This is how we think, learn, live. Either we age our thinking and blend it back into new thoughts or we must regularly go back and make current each of our essays, as Montaigne felt the pressure to do. You tell me which feels more natural.

***

In Marsala, Scicily, a solera method is used to make Marsala wine. The term in Italian that the winemakers use is in perpetuum.

***

Steven Church, talking about his essay “Seven Fathoms Down” (DIAGRAM, 13.5), explains “This is the third essay that I’ve written and published about the same event, each one a different essay, exploration, and attempt. I suppose it’s some sort of testament to the lasting power of such things, though not a testament I set out to write. It may seem like bullshit, but the essay found its way to the drowning and I didn’t see it coming. I just followed the pull.”

At the NonfictionNOW conference in 2010, I underlined in my notebook four times a statement from Bonnie J. Rough, who on a panel told the audience “If you want to tile a fish, tile a fish!” That’s great advice. So often I’ll hear someone – a student, a colleague — say that they can’t write about, say, their parents’ divorce again because they’ve “already written The Divorce Essay.” Nah, son. If that divorce keeps wanting to come up in your writing then let it. You don’t get just one shot at any subject. These things are a part of you forever and they are yours to use, to frame with and re-shape and reconsider, forever. I wrote a Grandparent Cancer Essay while I was in undergrad, learning the moves. I revisited the jaundice, the funeral, the anxiety in a different form years later in one of my first published pieces. I find myself revisiting it all again now that all of my grandparents are dead, now that my head is as bald by choice as that grandfather’s head was by nature, now that I’m cleaning his old work cap and wearing it around to protect my scalp.

You carry all of your prior essays with you from new draft to new draft. You just might not be aware of the blend percentage. The first essay you ever published is there in your most recent. Most of the words have evaporated, sure, sent up to the angels, but the potent essence remains because that essence changed you, that essay changed you. To even recognize it means it’s still there.

Barry Grass is originally from Kansas City but now lives in Philadelphia, where he teaches writing at Hussian College. His chapbook, “Collector’s Item,” was released in 2014 by Corgi Snorkel Press. Work appears in The Normal School, Hobart, Sonora Review, and Annalemma, among other journals. If you have a solera going, send samples for judgment to barrygrass@gmail.com

I used to say write like everybody you know is dead. It was my signature phrase, a gentle cudgel used to subdue the kind of self-questioning fear that often stunts a writer wading into uncharted waters. An exhortation to write wild, brave and free. Of course this was also when I wrote mostly about the living, when I wrote about the dead primarily as a passing referent, a milepost on my narrative journey. After my grandfather died. Before my grandmother died. When my cat, or aunt, or grade-school choir director was still alive. Mostly I wrote about those who would never read my words. I didn’t worry about my mean-spirited (but true!) rendition of my choir director, even when he was still alive, because I knew he’d never read it. And on those rare occasions when I did write about the dead, I wrote mostly flattering things, gentle odes to those passed on.

But when a longtime friend shows up in your newly-adopted state and drinks himself to death in your presence—a real-life Leaving Las Vegas played out over several weeks—then you will write the dead. The imperative of knowing, of witnessing—whether it be for atonement, or to honor, or to punish—you will write the dead. I am still writing the dead, although the story has trickled out on me at ninety pages—too short for a book, too long for an essay. An Essayvella?

*

Last summer I started writing by hand again, scrawling away in a gray composition notebook. Perched on the balcony of our carriage house apartment, surrounded by my potted palms and tropical plants, I let the summer breeze lull me into believing that I was playing the part of Hemingway in Key West, rather than Appalachian Ohio.

I hadn’t written with any serious intent in a notebook for six years, having finally trained myself during my MFA program to “be creative” on my laptop. I had been cursed with a stubborn certainty from the earliest years of my literary dabbling: a certainty that one could not—or at least I could not—type creatively in the same manner as I scrawled my barely-legible notebook odysseys. But after a decade of writing longhand, and then turning around and typing those words into a Word document, my wrists were perpetually sore, and my forearms plagued by a recurrent tingling numbness. Fear of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, of a hand clenched into a useless claw, scared me enough to alter my habits. So I pushed on past my ingrained superstition and discovered that in fact I could conjure expression from the percussion of my fingers on the keys. And every muscle and nerve from my knuckles to my shoulder blades thanked me.

Part of my decision to return to writing longhand was about trying to rediscover the joy of writing I used to know before I was a “Writer.” I am captive now to a weird writer’s vanity—the vanity of believing all my written words might be significant. It’s an absurd idea. I still generate far more future trash than I do marketable prose. But I no longer feel good “free-doodling.” Writing has become a commodity, or more accurately the time I have for writing is a commodity, and thus I feel the pressure to make that time count. Each word part of a sentence, part of a paragraph, part of a final essay to be submitted, part of a book of said essays to be offered up as sacrifice to the capricious gods of publishing. By getting “serious” about writing, I robbed the act of fun.

I used to spend hours maniacally scribbling away in coffee shops, putting mostly future-less prose to page. Sure I was going to be a writer someday. But I wasn’t there yet, and my 90s daydreams of writer greatness were barely more realistic than my previously imagined futures as a rock star or NBA power forward. Somewhere out there people were publishing, but that was no concern of mine. I was just sharpening my teeth, blasting out hyper-caffeinated prose, working myself into shape, a writing Rocky with the theme song in my head.

Then one day you publish something. Then you get into an MFA program. Publish a few more things. Become Nonfiction Editor for a lit journal. Go to some conferences. Get into a PhD program. Compile a big enough Word document to have a book or two or three. And where once I merrily dashed off reams of sketches without intent, now I agonize over all the work—the finished pieces still searching for homes, all my megabytes of stalled stories, embers of essay. Now I cringe when the word-flow dams up, when the “essayer” fails to bear fruit. Now I feel the pressure to produce. Now that I have stepped into the ring I have to confront, each time I write, the fear that it might not happen, that nobody is guaranteed a book contract just for finishing their work, that I might peak with a few good essays and then fade away…

*

I wrote the dead swamped in grief. I wrote in regret. I wrote in anger. Lambasted myself on the page for being unable to save my alcoholic friend. Lambasted him on the page for being unwilling to save himself. I wrote in forgiveness. I wrote in love. I wrote in remembrance. As the years scrolled by and the death receded back in the rear-view mirror I wrote with increasing detachment, when I wrote him at all. The tidal wave of early words slowed to a river, then a stream, then a trickle. I had said all I could say, disgorged my pages and turned instead to dabbling with rearrangements, trying to make the puzzle pieces fit into some semblance of a whole. I missed his April birthday this year, for the first time since his death. Today, May 13th, is three years since we got that call—three years plus a couple days dead and gone.

*

The past is malleable; we shape it and polish it until it resembles what is most palatable to our current selves, and our reflection of those previous incarnations. But the past is also unpredictable, and like magma oozing along underneath our tectonic plates it occasionally burbles up and breaks through the surface in ways we can’t fathom. Early October, the mid-George W. Bush years, waiting for a train at the Milan airport. It had been six years since that summer in Holland, my brief interlude as romantic expat abroad, and yet waiting for the train I could feel the swell of nostalgia and sorrow bursting up from a long-dormant core, spurred by the simple fact that it was the first time I’d been back in Europe since those events. Melancholy seeping from my pores like magma, and a visceral certainty that I could punch through the wall of the tunnel to find that other me, that other past lurking in shadows just outside the corner of my vision.

*

I think part of the allure of blogging is not just the immediacy of your words, the timeliness in response to current events, but also the immediacy of the self. This is who I am, right now. This is my life, my ideas, my brain on the page at this moment, date-stamped for perpetuity. This is the real-time wine and wafer; eat and drink and be one with me.

Because even in the quickest publication turnarounds there is normally a lag-time of months or sometimes years between those words you wrote at that moment when they were fully you, and the day those words go public. By the time my words see the light of day I am often tired of them, having rolled the Sisyphean literary boulder up the hill, writing, shaping, re-shaping. And then you see those words from this lag-time, where they are always that younger you, always a slightly different version, so that in reading yourself at the moment of publication you are reading your own history.

Some of my oldest Word documents pre-date the Millennium. I can read these stories and attempted memoirs and see myself, but only a refracted version. In a sense I reclaim my history every time I reread them, which is why it is simultaneously exhilarating and frightening to read those old pieces—or to delve into my old journals, which date back nearly a quarter-century. In the intervening decades those memories were sanded down and sun-bleached, but then I will re-read that passage from the journal of an angst-ridden 19-year-old and be viscerally reminded of who I was then, of that younger, smaller me that still exists in this older form, still forms the inner rings of the tree of me. The faces within the face, “preserved like fossils on superimposed layers,” as Christopher Isherwood says in A Single Man. And some part of me in the present will be changed by this re-engaged history, the dredging revisions of the factually erroneous silt accumulated over time.

*

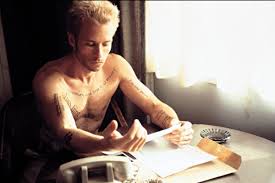

Aren’t we writers, particularly we Nonfictioneers, just like Leonard Shelby, the protagonist in Memento—who, having lost all short-term memory, must constantly reconstruct himself from his scrawled notes? Those important truths tattooed all over his torso, never to be forgotten. Aren’t we writers tattooing ourselves every time we publish?

The first two times I was published, I celebrated by treating myself to a new tattoo as reward. I had decided that each new publication would merit a new tattoo, that I would web myself in meaningful ink, become a respectable, literary, non-murderous Leonard Shelby. But I haven’t kept up that tradition. I meant to, but as subsequent publications happened I realized that they were not all of equal significance, and probably not all worthy of their own ink. And I had other things to spend money on, other people to consider. Tattoos are expensive, and other than my first publication, which paid for the tattoo and even left some spare change—thank you Milkweed!—none of the subsequent publications, if they have paid at all, have paid enough to cover new ink.

*

I have moved on, for the moment, to writing the living. Writing a book about my biological father, or more accurately about our relationship, and what it meant to grow up with a gay father in the 1980s during the height of the AIDS crisis. This is a story I’ve always known I had to tell, one that friends and professors alike have chided me for delaying. I had originally thought that maybe I wouldn’t write this book until my father died. That maybe out of respect for him, I ought to wait. But I realized something important, in the process of writing the book of the dead friend: it isn’t easier when they’re gone. In many ways it’s harder. What you might think of as the advantage of avoiding those awkward moments—they’ll never read it—are offset by the guilt one feels for writing them without the possibility of correction. Of being able to say anything you want. Of presenting their likeness without consent.

Part of me fears certain passages I’ve written already about my father, things that will surely hurt him to read. Part of me also fears the passages I haven’t written yet, the stories I’m slowly working myself up to, the ones I can’t imagine having a conversation with my father about. But we can do that. We can talk. And maybe in talking about these events, the stories themselves will become better, truer—more purely Nonfiction—as we hash out the differences in our memories to find a palatable shared truth. Isn’t that much more likely to be true than my singular version of events? Isn’t that more fair, more honest?

*

Those old Microsoft Word documents are in danger of becoming outdated, of living past the current technology’s ability to reach back and speak to them. It’s weird to think about because we always assume that technological improvements are without consequence, inherently positive. But of course with each passing year the incentive diminishes for the engineers at Microsoft to make sure that the newest version of Word is still configured to be compatible with antique, pre-Millennium versions of itself. And I keep ignoring the compatibility messages when I open one of these ancient scrolls, confident in the fact that we no longer live in the dark ages of technology when Apple and Microsoft spoke separate languages, warring across a tech channel like the French and the British. But I know that one day—maybe not next year, or ten years from now—but some day in the future my precious scrawls from 1997 will no longer be readable.

Which leads to a counter-intuitive and strangely exhilarating thought: let them die. Delete all. Delete them all. Like John Steinbeck burning The Oklahomans—his first attempt at The Grapes of Wrath—and starting over from scratch. Imagine the weightlessness of returning to a blank slate. Of digitally burning everything not already in print. Of saying thanks for all the practice, now toss those canvasses into the bonfire and begin anew. What if we could start over? What if we could erase everything we’d ever written, and truly forget? What would my next sentence be if I knew I would never re-read my old words?

Kirk Wisland’s work has appeared in The Normal School, Creative Nonfiction, The Diagram, Paper Darts, Electric Literature, Phoebe, Essay Daily, and the Milkweed Press Anthology Fiction on a Stick. He is a doctoral student in Creative Writing at Ohio University. He has not yet hit “delete all.”

In the grocery stores, dime stores, department stores of the New Orleans East neighborhood where I grew up, my grandmother stole and I lied. It became part of the rhythm of our days: Lala brought us into the English-speaking world, where the Americans talked like chirping, or was it squawking birds—I can’t pin down the analogous word, but I knew she didn’t like the sound of it, ese maldito ingles—and she spoke only Spanish, so I served as translator.

Very quickly I learned I must lie. Because at TG&Y off Michoud Boulevard, Lala deigned to purchase household items like toilet paper or detergent, but stole whatever tchotchke it was I wanted. In the check-out line the cashier might ask how we were doing, to which Lala would reply in Spanish, “I’m fantastic, you dummy, because I’m stealing from you, and there’s nothing you can do about it.” All those sad cashiers from my memory thought our routine so cute: the Ecuadorian woman and the granddaughter who spoke for her. That nice lady who complimented their haircuts, or the orderliness of the store. The woman who, no matter what inexplicable foreign sounds were coming from her mouth, was, according to her granddaughter, always having a nice day.

Lying in translation was simply part of my childhood. I couldn’t tell the world the truth about who Lala was. At home she was my world, and I hers—mi amor, mi vida, mi tesoro—but in public she made me cringe. She couldn’t even speak English, and it didn’t matter that she declined to learn by abstention because she hated the language so. All the world’s books, as far as I knew, were written in English. In this language, learning happened, so in my estimation, Lala refused to learn. I identified Spanish with fierce love and anti-intellectualism, and English where rules were made and followed. My English expanded through school and the limitless stories and worlds offered by books. My Spanish had one character, one plot, one god, and that was Lala. She both admired and begrudged my time with reading, and I knew the day would come when I was forced to pick a language. The more ensconced I became in the English-speaking world, especially when I was at home with Lala, the more of a traitor I became.

Sometime in my adolescence I permanently defected to English. I spent the first ten years of my life speaking Spanish every day, and in the subsequent twenty-five years I may have spoken three months’ worth of the language. I learned to love American boys and men in English, but because of Lala, I thought for some time I’d never be able to grapple with complex ideas in Spanish. In Spanish I only felt. In Spanish one was either the betrayer or the betrayed. Spanish was my dreamy past, and English the a more certain, stolid present and future.

The irony is that when I became a writer I had no interest in writing fiction, or at least in fictionalizing our story. I didn’t want to create a zany Hispanic grandmother performing zany stunts. I had to write her. But through force of childhood habit, I was out of practice in telling her truthfully. And for all the “what is truth in memoir?” debates surrounding this genre, I think the foremost strategy for writing it is pretty straightforward: try not to lie. Tell the truth as you remember it: don’t make more or less of anything or anyone, including yourself. For me this has been complicated by not only my early propensity to lie, but that the truth as I remember it happened in Spanish. Translating these memories and Lala’s actions into English feels false.

In considering this false feeling, I’m reminded of a moment in Richard Rodriguez’s memoir Hunger of Memory, when as a boy he’s asked by a friend of his, a gringo, to translate what Rodriguez’s Mexican grandmother has just yelled out to him from her window: “He wanted to know what she had said. I started to tell him, to say—to translate her Spanish words into English. The problem was, however, that though I knew how to translate exactly what she had told me, I realized that any translation would distort the deepest meaning of her message: It had been directed only to me. This message of intimacy could never be translated because it was not in the words she had used but passed through them. So any translation would have seemed wrong; her words would have been stripped of any essential meaning. Finally, I decided not to tell my friend anything. I told him that I didn’t hear all she had said.”

What Rodriguez expresses here is the untranslatability not of language, but of people and their intimacies. I feel already the person I’ve sketched so far is more Latina imp than Lala. How to capture her largeness, her generosity followed by her startling moments of pettiness, without allowing the reader to hear and understand her voice directly? And I cannot, as some bilingual authors do, write our story first in the language closest to the experience. My Spanish is no longer, and perhaps never was, that strong. Today I can still tell Lala I love her and narrate the changing details of my life; I can still make her laugh. But if she were unable to hear, I couldn’t write any of it for her in a language she could understand.

*

In his 1800 essay “On Language and Words,” philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer proposes a specific marker for the mastery of a language: when the speaker is capable of translating not words but oneself into the other language. This issue of retaining one’s personality and authentic self across languages remains troubling because in my distance from Spanish, I’m not sure how much I can accurately define who I was when I lived in that language, or who I am within Spanish even now. I recall my young, primarily Spanish-speaking self as devoid of personality, as completely dependent on Lala’s love alone, as a vessel in which the only thing more powerful than the will to please was the silently-brewing mutiny over my leader and her language.

When I think of who I am in Spanish now, when I speak it with Lala, I wonder if I’m still more who she would like me to be—the loud, brash, fearless woman she once was—than I actually am. In Spanish I search more vigilantly for the humor, the absurdity, the magic of living, I find colors and sounds bolder and more daunting, I hear in every sentence a song. It’s an exhausting way to live, which may be why I don’t do it (or speak it) often. To be an always-on vaudevillian in one’s second language is no small task.

With that in mind, let me translate a joke from Spanish.

Last winter I visited Cuba to prepare for a writing exchange this summer between my students at the University of Alabama and Cuban students at the University of San Geronimo in Havana. As part of our exploration, a colleague and I visited the Tropicana Club, famous for its lush tropical gardens, stunning light shows, and nearly-nude dancers.

We arrived early and as I was served my first drink, an icy Cristal cerveza in its tall green bottle, a bird shat all over the left side of my head, shoulder, dress. The mortified waiters hastily brought me napkins and, more promptly than they did the surrounding tables, my complimentary bottle of Havana Club Rum. Everyone apologized profusely: disculpeme, perdoname, que pena. But one waiter knew just what to say as he dabbed my shoulder with a moist napkin: mejor un pajaro que un caballo.

Better a bird than a horse.

And the waiter’s joke made me laugh. Made me forget all about the bird shit. But the more I’ve thought of the joke since, what it would be like if someone told it to me in English after I’d been shat on by an Alabamian bird, I don’t think it would hold the same weight. I don’t know if it would be as fun. Magical realism isn’t just a writing genre in Latin American cultures: it’s a way of seeing the world. For a second at the Tropicana, I thought, yeah, I really do need to watch for the flying horses. No: los caballos que volan.

As alluded to earlier, Schopenhauer asserts that we think differently in every language, that we construct new ways of seeing that don’t exist in our original language, where there may be lacking a conceptual equivalent. A further inference might be made, which is that we feel differently in every language, too. A bird will more readily shit on me in Spanish, in the language where I’ll more readily laugh at it. It makes sense for me to momentarily fear flying horses in Spanish, as ludicrous as that sounds when I’m translating it now.

*

When I write about Lala, I could tell just the facts: when she was five years old she watched her mother die of tuberculosis, choking on her blood; she was taken in by three vindictive aunts who chopped off her hair, made her kneel on rice so often she rarely had skin there; she’s a raised eyebrow away from five feet tall, but in my memory she’s massive, capable of flooding the kitchen and drowning us with her tears when she cried, and she cried often, in her fear and her anger that I didn’t love her enough. In her I saw all those sad stories manifested in her body. She could literally drown me. I did my best not to make her cry.

That’s the problem with facts. The truth of how I read her and felt about her slips in around them.

*

Translating words and phrases from Spanish to English, while a vigorous academic exercise, isn’t my greatest difficulty in writing about my past with Lala. What’s most confounding is finding a way to translate her actions. What if I told you of one of the specific ways in which Lala loved: how she kissed me as a child, kissed every place, every powdered part? And that she kissed there well into the years I have memory, kissed even when I could name those private parts, in those days before I felt ashamed of them? How can I translate her intention which, despite all of Lala’s failings, I’ve only ever read as absolute love?

I can tell you that in English-speaking MFA workshop critiques, Lala’s love has been compared to the destructive, perverse one found in Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss, the memoir in which the narrator recounts her love affair with her biological father. What happened to me was abuse, I’ve been informed, and was advised by some peers not to write about it. Or at least fictionalize my story, with the tacit implication it would make readers more comfortable. Is it through these kisses, they asked, that I want to be known as a writer?

Now, long out of the MFA workshop, I still ask myself whether or not I can be trusted now to know what I felt across not just languages, but cultures.

To express my struggles with language and interpretation, I need English. To express the most important parts of myself, how I learned to love and how I learned to be, I need Spanish.

But what does it mean if my facility with Spanish isn’t what it used to be? Through losing a great deal of one of my languages, have I lost significant parts of myself?

*

Now just one more story (or is it a riddle, or a joke, a puzzle?), one that Lala told me dozens of times growing up. It’s the refrain of my childhood: el cuento del gallo pelon. The story of the bald rooster. Here’s how the story often went:

Lala: Do you want me to tell you the story about the bald rooster?

Me: Yes!

Lala: I didn’t say anything about yes. I asked you if you wanted to hear the story of the bald rooster.

Me: Please, just tell me!

Lala: I don’t understand what you mean by please. I’m simply asking if you want to hear the story of the bald rooster.

Me: I want to hear the story! You’re getting on my nerves!

Lala: Here you sit talking about nerves and stories when I’m trying to tell you my story of the bald rooster.

And on and on this non-story would nightmarishly go. Through this story neither teller nor listener ever leave the question—the story is never finished. It requires perhaps the devotion of a child to continuously ask for more when resolution is this improbable, and a lover of language to begin the circuitous dialogue in the first place.

This story, as is turns out, is an appropriate metaphor for my work on the Lala memoir. I’ve been writing parts of it for eleven years, off and on. Friends say “tell me more, tell me more,” and I respond, I am telling it. Lala. Memoir. What are you writing? I’m writing it. This story. That story. And on and on the dialogue goes with no resolution.

I don’t know if there’s any solution to the “how do I write this memoir?” dilemma other than to write first and worry over potential problems later. If there’s a solution to my own, it may be in its tentative title. Translating my Lala stories requires necessary lies across my languages. Though translation may be maddening, may feel false, may require stops and starts, the alternative is the silence Richard Rodriguez answered with when asked what his grandmother had said.

My grandmother is called Lala. I want to tell you what she said and what she did. How her love could be frightening, and sublime. Through the best words I can find, if not always the exact ones, I’ll try to show you.

Works Referenced

Rodriguez, Richard. Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez. New York:

Random House, 1982. Print.

Schulte, Rainer and John Biguenet, eds. Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida. Chicago: Chicago UP, 2002. Print.

Brooke Champagne was born and raised in New Orleans, LA and now writes and teaches in Tuscaloosa, AL. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Los Angeles Review, New Ohio Review, Prick of the Spindle, and Louisiana Literature, among other journals. She is at work on her first collection of personal essays, and her memoir about her grandmother, Lala.

I used to think I was born for big

things. I would be well-known,

admired. Change the world.

But fame is for the dead. Van Gogh,

Jesus,

me.

Once, Francesca Cuzzoni refused to

sing the first aria in Handel’s

opera. Madame, he said, I know you

are a veritable devil, but I would

have you know that I am Beelzebub,

chief of them all.

Handel was either a musical genius

or, if Sir Isaac Newton can be

trusted with anything, unremarkable

save for the elasticity of his

fingers.

Then Handel took the

soprano by the waist and swore that

he would throw her from the window…

Picture

Michelangelo in a

windowless room

late at night. Picture him by

candlelight, working tendon

from bone, muscle from muscle

as if untwining lengths of

braided hair.

Or Professor von Hagen in a

black leather fedora exchanging

fluids for plastic in the most

splendid parts of the human

body:

lungs laced with purple veins,

translucent sheets of flesh.

Watch bones bend in his hands.

Watch him fashion, form, sculpt, create.

What is art if not tender

revelation? What is art if not

dedicated to love? Look to the

body. Touch it. Run your

fingers over the shapes of it.

Taste it. Smell it.

The ecstasy of an ear drove Van

Gogh to madness, forgetting

hunger and thirst in the sun

with his canvas empty before

him.

When I connect the freckles on

the back of my left shoulder, I

have a Chagall. Aqueous sky.

An anchorless range of

mountains. A tilty, four-layer,

rum chocolate cake.

What is it?

A man, drunk, is dismembered by a

passing train. His wife buys a red

dress, her heart filled with wet

ash. The dress is blue red, cold red.

She licks sugar from her fingers.

The scrape of her shoes on cement

make her think of rats.

She sits in the kitchen with her feet on a stepstool

wearing the same expression she puts on for church.

Sir Isaac Newton heard the opening of the dawn.

Thomas Edison was afraid of the dark.

Lord Carnarvon and his dog died at the precise moment

the power failed in Cairo.

Think of the clipped light caught

in the wife’s kitchen window:

a measure of blue,

a stitch of green,

a ribbon of pink across

the bridge of her nose.

How it comes on swift wings,

such small disturbances of

peace.

Traci O. Connor is a novelist, poet, flash-memoir writer, and author of the short story collection, Recipes for Endangered Species (Tarpaulin Sky Press). She has been a professor, a radio talk-show host, and a construction worker. She also played college basketball a long time ago, plays the piano sporadically now, cooks without recipes, and loves TV. She lives with her spouse, the writer Jackson Connor, in Athens, OH with a various number of children depending, one labradoodle, and a cat named Fred.

“I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.”—Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”

Like many writers, I come to the lyric essay from a background as a practicing poet. And the poetry I’m known for practicing often is written in received forms, like the sonnet or triolet, and as such, I’m often tapped to teach poetic forms to students. My experience with forms is why, while trying to stretch my teaching and my own writing by teaching a hybrid forms workshop last semester that included the lyric essay, two things struck me.

There’s an oft-repeated (at least by me, to my students, ad nauseum) saw that originates in a letter from Theodore Roethke: “‘Form’ is regarded not as a neat mould to be filled, but rather as a sieve to catch certain kinds of material.” [1] Sonnet-sieves catch short arguments or questions to be answered. Villanelles and triolets strain out all but the most obsessive turnings-over of topics.

Since this is the mindset with which I come to writing, as I was teaching my class, I found myself thinking of the lyric essay as its own poetic form – asking not how to define it as a “mould,” but trying to determine what kind of material is suited to its sieve.

To do so, it might help to review some of the qualities and structural features of the lyric essay, in order to think about what kinds of content they might facilitate. The lyric essay represents a collision of opposites: poetry with prose, music and meaning, the realistic with the speculative. It often presents its material content through parataxis, juxtaposition, fragmentation, and collage in a way that makes representation a dynamic process. Its disjunctive leaps, hesitations, ellipses, elisions, non sequiturs, and self-contradictions subvert the privileging of writing as the product of the Romantic unified “I.” It may suppress linear progression in favor of circularity, meditation, imagination.

Yet the lyric essay balances this instability by keeping the reader’s attention at the level of language with lexical and syntactical richness, repetitions of sounds, words, phrases, motifs, and braids. What’s important emerges through accretion of patterns, either by imposing a pattern on what otherwise seems to be chaos, or by revealing an underlying or hidden pattern. The deceptively simple packaging of prose uses brevity, the speed of its progression, and often colloquial language to persuade the reader to quickly accept any odd or surreal details and/or to move across juxtapositions assuming connections, yet can make surprising turns even more surprising.

As a result of these qualitative and structural features, the form of the lyric essay “sieve” seems to attract or catch the following kinds of material:

The second thing that struck me, after considering the lyric essay as a poetic form, was its similarity to another poetic form that emerged in American poetry around the same time. The lyric essay was first named by Deborah Tall, then-editor of Seneca Review, in 1994 in a note to John D’Agata, and the journal devoted at least part of its space to the form starting in 1997. In 1992 Kashmiri poet Agha Shahid Ali introduced contemporary poets to the medieval Persian form, the ghazal, in an essay “Ghazal: The Charms of a Considered Disunity,” began publishing his own, and prodded his colleagues to write poems in the form, which he published in the 2000 anthology Ravishing DisUnities: Real Ghazals in English. [5]

For those unfamiliar with the ghazal: it is a form written in couplet stanzas, of at least five couplets but with no maximum limit. In the opening couplet, both lines end with short refrain immediately preceded by a rhyme; in subsequent couplets, only the second line has the rhyme and refrain, and the final couplet often is signaled by incorporating the poet’s name. (For several examples, see the Poetry Foundation at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/browse/#poetic-terms=53). Yet a hallmark of the form is its seeming disunity: as Ali explains, “The ghazal is made up of thematically independent couplets held (as well as not held) together in a stunning fashion…. Then what saves the ghazal from what might be considered arbitrariness? A technical context, a formal unity based on rhyme and refrain and prosody.” [6]

In both the ghazal and the lyric essay, what’s important is what’s emphasized by pattern, yet each form gives the writer as much or as little room as desired to approach the topic from any number of angles. The effect may be a cohesive progression building on the central theme or refrain idea, or disjunctive fragments linked only by the theme/refrain’s central hub. Both invite the reader to engage with the form, co-creating meaning in determining how the piece hangs, or doesn’t hang, together.

In some examples of the lyric essay, the fragments on the page visually resemble the ghazal’s brief couplets, as in Fanny Howe’s “Doubt” or this excerpt from Claudia Cortese’s “The Red Essay”:

1) Setting: The barn. Sometimes, I can’t remember if there were stars, fall air

clear or smoky, the shape of the moon’s face.2) I read Perrault’s moral to my students: Attractive, well-bred young ladies should never talk to strangers, for if they should, they may well provide dinner for the wolf.

4) Afterward, Bill died, and I was glad. Afterward, he sang Meatloaf to me and I held him and laughed.

1.5) Other times, I can see the barn door wide open, grass below soaked in starlight. I could have

screamed or clawed. I dreamt saltwater

taffy, sister’s sticky kiss, how we kicked

pigeons with our skirts over our heads.I worried about his feelings, that he’d feel rejected.

3) I said, Let’s go back to the house. I’m cold. Please. Stop. He said, It won’t take long. I won’t go in all the way. We negotiated. What do you name that? [7]

In this excerpt, Cortese holds in tension trauma memoir and fairytale, anecdote and critique, prose and poetic fragments, linked by the motifs of the wolf and vulnerable girl, and by the proper nouns she does name – Perrault, Bill, Meatloaf, etc. – even as she struggles to name her experience. Other lyric essays may not use fragments, but incorporate thematically or stylistically autonomous parts to achieve tension. Each section of Nicole Walker’s brief triptych “Fish” approaches its common subject from a different point of view and a nonfiction style – nature documentary, memoir, food writing – and but ties the three sections together through motifs and words that echo throughout the piece: the act of straining, “flesh,” “hold,” “circling.” [8] Likewise, Brian Doyle’s moving 9/11 essay “Leap” links a collage of eyewitness accounts, apocalyptic biblical quotes, and meditative speculation via the repetition of “hand in hand” to transform the horror of bodies leaping from the Twin Towers into a prayerful, elegiac image. [9]

The above examples lend themselves to what Wordsworth called “process of mind”: they demonstrate the experience of a mind exploring and discovering a complex topic, and they engage the reader in this process. The fact that both the lyric essay and the ghazal reached a critical mass in popularity at the same moment may signal a readiness for forms which, as Agha Shahid Ali puts it, “evade the Western penchant for unity,” whether unity of speaker, style, or source – forms which allow for a multifaceted exploration of its content. To return to Ali, as he phrases the question, “Do such freedoms frighten some of us?” [6]

Sources:

[1] Kinzie, Mary. The Cure of Poetry in the Age of Prose (U Chicago P, 1993). Print.

[2] Lindner, April, “Eloquent Silences: Lyric Solutions to the Problem of the

Biographical Narrative,” The Contemporary Narrative Poem: Critical Crosscurrents, ed.Steven P. Schneider (U of Iowa P, 2012). Print.

[3] Lopate, Phillip, “The Lyric Essay,” To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary

Nonfiction (Free Press, 2013). Print.

[4] Sajé, Natasha, “A Sexy New Animal: The DNA of the Prose Poem,” The Writer’s

Chronicle, March/April 2012. 33-49. Print.

[5] Ali, Agha Shahid, “Ghazal: The Charms of a Considered Disunity,” The Practice of

Poetry, ed. Robin Behn and Chase Twichell (New York: HarperPerennial, 1992).

Print.

[6] —, “Ghazal: To Be Teased into DisUnity,” An Exaltation of Forms, ed. Annie Finch

and Kathrine Varnes (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2002). Print.

[7] Cortese, Claudia, “The Red Essay,” Mid-American Review (34:1, 2013). 25-6. Print.

[8] Walker, Nicole, “Fish,” Quench Your Thirst With Salt (Zone 3, 2013). Print.

[9] Doyle, Brian, “Leap.” Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction. Lex Williford. (Touchstone, 2007). Print.

Heidi Czerwiec is a poet, essayist, translator, and critic who teaches at the University of North Dakota and edits poetry for North Dakota Quarterly. She is the author of three poetry collections including the forthcoming A Is For A-ke, The Chinese Monster (Dancing Girl Press), and the editor of North Dakota Is Everywhere: An Anthology of Contemporary North Dakota Poets. Recent or forthcoming work appears in Barrow Street, Waxwing, and Able Muse. Visit her at heidiczerwiec.com

—

An independent narrative and immersion journalist, Maggie Messitt has spent the last decade reporting from inside underserved communities in southern Africa and middle America. Typically focused on complex issues through the lens of every day life, her work is deeply invested in rural regions, social justice, and environmental sustainability. Messitt currently resides in southeast Ohio where she’s completing her doctorate in creative nonfiction and working on her next book, a hybrid of investigation and memoir, the story of her aunt, an artist, missing since 2009. The Rainy Season: Three Lives in the New South Africa (April 2015) is her first book.

First, you slip your arms through the overlong sleeves of a brand new white jacket. That new clothing smell: bleached cotton, crisp canvas. The discovery of curious leather straps and metal buckles, the function of which are yet unclear.

The discovery—stranger still—that the sleeves are sewn shut.

For argument’s sake, let’s say this jacket has a particularly tight fit. Let’s say that, straps cinched and buckles fastened, the snug garment pretzels your arms across your chest, left arm over the right, pressing your thumb-knuckles into your ribs, a tight vertical belt running from your navel to your coccyx.

Imagine, if you will, that you’re literally tied in a knot.

Straitjacketed.

Now, let’s say you’re hanging upside down on the stage of a vaudevillian theatre. Dim chandeliers sprout from the ceiling/floor like ornate stalagmites. Your head beats with blood-thrum; your hair hangs like single, limp wing. Stage lights hot as stove-tops, circles of your own sweat darkening the dusty stage floor.

Picture, now, a live audience—three hundred inverted heads.

You writhe and strain against the restrictive coat, thumping and wriggling, skin burning and chaffing, like a pupae tearing free from its silk casing.

You have sixty seconds.

O—-O

Two years ago I had coffee with an editor of a well-regarded literary journal, known mainly for publishing high-caliber literary fiction. We sat down to talk about an excerpt from my forthcoming memoir that I hoped he’d publish in special-themed edition of the magazine. The excerpt describes the narrator’s emotional descent and increasing self-destructiveness after a break up and a traumatic robbery incident. Each section of the piece is prefaced with an actual surf report, which act as a kind of emotional barometer: as the narrator’s psychological state becomes more dire, the surf grows larger, more life-threatening. But at this editor’s request, I’d stripped the surf reports from the piece, to make it more conventional, more capable of standing alone from the larger book. Because I so wanted the excerpt to appear in the magazine, I was willing to make these changes, to excise the one element that I felt (and still feel) makes the chapter most formally intriguing.

In the small talk before we got down to business, the editor mentioned something about how he likes authors who write with a great deal of restraint.

Only after the magazine rejected the revised piece, a month or so later, did I realize this comment had been likely been aimed, more or less directly, at me. Not only had I wasted my time on a fruitless revision, but I’d also been relegated, apparently, to a category of writers who do not write with a great deal of restraint.

The rejection left me in the dark for a day or two, the embarrassing little Fourth of July sparklers of my own insecurity singeing the thin skin of my inner wrists. The truth is I’m attracted to writers who use restraint, who place themselves willingly in something of a literary straitjacket. I’m thinking of Amy Hempel’s stunning self-control in The Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried, an essayistic short story in which a flawed young narrator visits her terminally ill friend in the hospital. Cemetery manages to be satisfyingly emotive without a shred of sentimentality or cliché; there is zero tugging at the conventional heartstrings, but it’s also deeply felt and paradoxically generous. It’s rumored to be Hempel’s first published piece—edited by Gordon Lish, that dark emperor of restraint—and it’s as close to a perfect short story as I’ve read.

O—-O

Several months after its release, I was invited to visit a friend’s book club, to discuss my memoir. We had a lively conversation, at the end of which one woman asked me the following question:

How do you know whether or not you’ve given too much of yourself away?

She was a doctor, and struggled with knowing when and how much of her own stories to share with patients. She was interested in discussing larger questions of How much do you reveal about yourself? and When do you to maintain professional boundaries?

I’m afraid, though, that I took her line of inquiry too personally, as a condemnation.

I believe firmly in making oneself vulnerable on the page; I’m a constant proselytizer of this gospel. But having released an emotionally raw memoir, these days part of me feels prone to want to write with more restraint, more camouflaging, more obliqueness.

When does vulnerability become weakness, I find myself constantly wondering—and have I crossed that line?

The answer is, it probably depends on who’s reading your work.

There are times, like when I received an email from a thirty year-old schoolteacher in New Jersey, with the headline “Your Memoir Saved My Life,” that I’m glad I wrote what I did. There are other times—like during the book club Q&A session, or when I read certain online reviews (something I’ve since quit doing, as a strict rule), or when I think of my male in-laws reading my memoir—that I’m not so sure.

O—-O

Restraint and seclusion were often used to control the behavior of people with mental health conditions. However, in recent years, clear consensus has emerged that restraint and seclusion are safety versions of the last resort and that the use of these interventions can and should be reduced significantly.

O—-O

I want to make sure I don’t conflate the concept of restraint with the practice of utilizing literary constraints. As so many of us know, writing with self-imposed constraints can be freeing. In a recent interview with author Steven Church, while discussing an essay in which he limited himself to riffing only about the topics “shoulders” and “crowns,” he said the following: It is a bit paradoxical, I suppose, that putting handcuffs or constraints on my thinking also allowed my thinking and research and essays to expand in fascinating ways while also leading to many moments of discovery. . . I highly recommend it.

O—-O

Lately there’s been quite a lot of dissing of the confessional mode, dissing of memoir, at least in high-literary circles. Having just released a memoir, maybe I’m just overly sensitive to it. In a recent interview, Megan Daum said something to the effect of I don’t confess, that makes it sound like I did something wrong. Shortly afterward, in another interview, Charles D’Ambrosio said something disparaging about writing in a goopy confessional mode. These are both writers who I imagine would eschew the label memoirist in strong favor of the term essayist.

I would argue that 90% of the time we talk about “confessional writing” we’re talking about work that reveals mental dysfunction, addiction, intense emotional states, etc. I’m thinking now of O.G. Confessional Poets like Robert Lowell, who wrote about his struggle with mental illness in Life Studies. The label of “confession” often also extends to admissions of having been raped, or sexually abused, or otherwise victimized. Or, in the case of St. Augustine, of lust and promiscuity. So, one could argue, the railing against “confession” is also a covert stigmatization of these issues, as not ok subjects for polite social or artistic discourse.

But I tend to agree with Megan Daum that confession is maybe not the right word, that it has conservative Catholic undertones that imply “sin” and “guilt.” And as for D’Ambrosio, who is himself a Catholic, I agree that goopy confessions might be best reserved for the privacy of a confession box or a therapist’s office.

Maybe what we’re going for is just plain old expression, a word I do like, with its connotation of pressing emotions away from our bodies, rather than aiming the barrel inward—the opposite of depression.

O—-O

In the comments section of a recent online article about the film version of Wild, a male commenter/troll wrote something to the effect of Cheryl Strayed must be stopped. Stopped, as in restrained. As in: restrained from sharing so many of the details of her life in such a public way. As in: restrained from achieving such stratospheric success for having been emotionally honest, and talented. In a recent radio interview, Strayed said, half-jokingly, that if she’d known so many millions of people were going to read her book (including, presumably, the mostly male trolls who harass her) she never would have revealed so much about herself.

O—-O

I sort of don’t want to tell you something, though I’ve long since let the secret out of the bag.

I’d kind of rather just hang here, knitted up safely in my strappy canvas jacket.

In the section I was hoping the aforementioned literary magazine would publish, I admit to having a very hard time transitioning onto some antidepressant medication in the wake of having a gun shoved in my face. During my conversation with the editor, he mentioned that my revelation re: the meds was maybe a bit too much, too revealing, too vulnerable. Too heavy. I suspect this was part of the reason they ultimately rejected the piece, even after asking me to revise it.

I’m certainly willing to entertain the idea that the piece didn’t work outside the context of the larger memoir, or that the revised version just wasn’t all that good.

But I’m also left with the feeling that these things—e.g. an adult human being actually really needing some help—are not to be discussed. At least not in work that might appear in the pages of a well-regarded literary magazine.

O—-O

Straitjackets were invented in France, of all places—that bastion of libertè and equalitè—by an upholsterer named Guilleret, working on contract for the Bicetre Hospital in 1790. Most historians consider straitjackets a major improvement from the ropes and chains previously used to restrain the mentally disordered. Such implements included handcuffs, which have been around in some form since the Bronze Age.

Across the channel, one hundred and some odd years after the invention of the straitjacket, T.S. Eliot formalized his concept of impersonality in poetry, otherwise known as the objective correlative. His proclamation decreed that a poet’s personal emotions should never be stated directly on the page, that instead the poet must find some object or image suggestive of them—e.g. a patient etherized upon a table—and only then can s/he evoke the same feelings in the reader.

As William Carlos Williams later put it, there should be no ideas except in things.

The objective correlative, one could argue, is a kind of straitjacket designed to keep things from getting too messy, to restrict the writer from revealing too much or embarrassing himself with vague sentiment. T.S. Eliot went so far as to wield it against Shakespeare’s character Hamlet, whom he felt was too unrestrained in his emotional outbursts.

The objective correlative is absolute doctrine in most contemporary university writing departments—this device that was instituted nearly a century ago by a brilliant but repressed man from St. Louis, living in perhaps the most emotionally reserved culture on the planet.

(The etymology of the word reserved traces back to England in the 1650’s, meaning self-imposed restraint on freedom of words or actions; a habit of keeping back the feelings.)