Seven

Lately, time seems to be all I think about on a personal and philosophical level. Perhaps it’s because I notice age slowing down the ones I love. Perhaps I discovered more gray nose hairs in my right nostril and that freaked me the hell out. Or perhaps this awareness of time comes when our sense of self gets challenged, like mine has in the last few months.

When you think about time, you are really thinking about death.

Ninety-one

This should not be a surprise to you: Time rules us. We do not and cannot control it. As much as I wanted to possess superhuman powers when I was a teenager—like slowing time with a snap of my fingers when my eighth grade crush Brenna Murphy—having undergone wonderful changes of the body—ran towards me, I could not. I lived by the laws of time, subjected to a two-month relationship with Brenna that involved hand holding, park kisses, and her chasing me with a butcher’s knife.

Time is an unavoidable fixture in our existence. We live by it. We sleep according to time. We arrange meetings, lectures, and classes by time. We watch our favorite shows and take our medication at certain times. How often do we check the time of the day? How often do we ask, “What time is it?” How many times do we wish for more time to write a meditation on time, a memoir about a certain time of life, or a letter to an ex-wife or a dying parent? How many times have we wished for more time to do all the things we want to do?

It is not surprising then that the English lexicon is infested by clichés of time. All in due time. There’s no time like the present. Time after time. Time and again. Time flies.

Nor is it surprising that writers and philosophers have been contemplating time since the dawn of time.

From Plato: “And so people are all but ignorant of the fact that time is really the wanderings of the sun and the planets.”

Sophocles: “Hide nothing, for time, which sees all and hears all, exposes all.”

St. Augustine in his Confessions: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.”

Twenty-five

The holiday season approaches. The landscape of America changes. The department stores are glittered in silver and gold garland. Santa is everywhere with his jolly cheeks and cotton-tipped hat. Bing Crosby croons holiday songs in the grocery stores, and bells beg for donations in a red pail.

Holidays are ripe for nostalgia. They are moments to assess our lives. We move forward. We move backwards. We think whether this holiday will be better than the last. We begin, as most children do, to dream of new toys Santa will sneak under the Christmas tree next year.

Even as a Buddhist, I’m inundated with holiday moments, memories from years past. A mental rolodex of Christmases and New Years. My father and his new Polaroid. The shutter and flash. The seconds it takes for the picture to materialize. Aunty Sue carving the Chinatown duck, her hands and knife thick with yummy grease. My mother’s soft snores on Christmas Eve after working a double shift at the hospital.

Eight

Before my mother moved back to Thailand, she gave me over two large boxes of photo albums. I went through each of them, trying to remember our former lives, stilled in photographs. What struck me most were not only the photos of our holidays, but my mother’s perfect print next to the yellowing photos. The date. The time. The place.

I’ve seen this impulse to record in other photo albums. What is this need we possess to not only capture the photo, but to log it in with numbers? Do the numbers mean anything?

I am standing in bright neon pants that flare at the bottoms. A blue octopus is on my head. Behind me is the Christmas tree, delicate ornaments glinting from the camera’s flash. I’m smiling. Two of my front teeth are missing.

Beside the photo, my mother’s writing: Ira, age 3, living room, Oak Lawn, Illinois, 12/25/79. He is happy.

Two Thousand

Every time I see numbers in an essay, I hear Dick Clark’s voice counting down to the new year. I also think of the apocalypse. I know these two things don’t go together.

Thirty-seven

I’ve been through thirty-seven Christmases and thirty-seven New Years. After a while, it’s one big mess. A fun, festive mess, like discarded and torn wrapping paper, like bows and ribbons on your pets.

One Point Eight

Every year I go to Thailand to visit my mother and Aunty Sue. They are eighty, and now time has slowed their walks, hunched their backs, clogged their ears, much to my impatient dismay. Now, I help them in and out of cars. I hold them as they walk up and down stairs.

At the Chiang Mai Airport, they play with an eight-month-old baby, who smiles and gurgles and drools happiness. They make faces at him and coo. They caress the smoothness of his skin.

I watch them and think, this baby is me. Both my mother and aunt are really cooing at me, or a version of me that no longer exists, but one catalogued in their memory, a moment where they have stilled time to relive, a joy that can never return.

But it has.

Everything they do, everything they eat, is in relationship with the past. It’s in the manner of their speech. In the moments when they begin, “Back then….” It’s even in how they hold me—longer, stronger, never wanting to let go.

A Gazillion

The memoirist, like my aging parents, does not want to let go either. It’s as if she is in a sci-fi movie, where her memories are displayed in front of her. And she uses her hand to arrange them, moves them around, throws some out. She rewinds. Fast forwards. She does this so that she can create a narrative timeline. The first steps of telling a story. The first steps of understanding.

Forty-one

I’ve become a reluctant fan of the writer David Shields, author of the controversial book, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto. I say reluctant because of his stance on the genre of my beloved memoir. If one were to flip through Reality Hunger one would find an array of criticism against chronology and narrative storytelling. One would find Shield’s championing of the lyrical structure of fragmentation and mosaic movements. One would find lines like this: “Anything processed by memory is fiction.” Or, “Everyone who writes about himself is a liar.”

Reality Hunger is Shield’s own manifesto, his way of understanding the world—he has said as much in interviews—but part of me turned into that gruff Chicago boy from ages ago, that Chicago boy defending his turf, his little tiny patch of city green because I had just published a memoir about being raised Thai in America and it was chronological and for the past ten years I have devoted myself to this genre. I was like, what the hell, dude? You best step off.

But what also lingered underneath this sentiment was a voice that said, “David’s right, you know.” He is. To a point.

I didn’t completely disagree with Shields. In fact, I marveled, like him, at essays and books that have challenged the traditional structure of memoir—Lauren Slater’s Lying, for example, or Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of a Staggering Genius. I embrace, like him, the “collage” as structure, disagreeing, however, with his assertion that collage is “an evolution beyond narrative,” but rather another option for a writer trying to find form and function on the written page. I found that I loved the books Shield’s loved, like Geoffrey Wolff’s Duke of Deception, and loved the books he didn’t, like Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life.

After reading his manifesto and hearing him speak on numerous occasions—he is quite brilliant—I wanted to see how his manifesto translated into his own work, so I picked up The Thing About Life is That One Day You’ll Be Dead.

Shields uses two threads to tell his story, like a braided essay—one orders the memories he has of his father, never chronological, but fragmented and scattered in no specific pattern, and one discusses how the body ages and begins to deteriorate over time. Let me warn you: If you are a hypochondriac and do not want to be aware what happens at what age, avoid this book. I found myself counting the amount of hair I was losing and gauging my libido on a daily basis.

Despite Shields’ diatribe against chronology and memoir in Reality Hunger, The Thing About Life is That One Day You’ll Be Dead is both chronological and a memoir. (David Shields’ nose is probably itchy right now.) It is not chronological in the traditional sense, nor is it a memoir in the traditional sense. In his book, Shields’ father escapes the linear because there is nothing linear about him. He is an enigma, a delicately curved question mark. Shields can’t reconcile what he feels for his father, whether it is hate or deep affection. His memories of his past jump back and forth through time, in no logical sense. But we are never lost in the book because Shields has given us chronology, has imposed order, by telling us about time in the biological sense. Our bodies—our physical presences—are about time. It is the one constant thing that makes us human.

Twenty-Three

David McGlynn, “Traumatized Time”: One of the magical qualities of creative nonfiction…is its ability to travel through time, to leap without preamble or warning from the narration of particular past events to the immediate and universal present.

One Billion Eight Hundred Thirty Three Million Five

Maybe the countdown to a new year and the countdown to the apocalypse isn’t so different. If there is a beginning then there is an end.

One

I have to tell you this story. And it has to be chronological.

There was once a boy so insecure with his life, he took diet pills, believing that they would magically make him better. But he did not know what better meant. Skinnier? Happier? Normal-er? He didn’t have the sense, this boy, to ask the questions necessary in understanding the self. He didn’t want to understand the self. He didn’t want to be anywhere in his head, where thoughts whirled and stabbed, where shadows sought to suffocate. He wanted a quick fix, a present-moment action. What’s easier than popping pills? What’s easier than taking a handful of them and washing it down with a swig of beer?

Oh, that boy, oh how he smiled and laughed, oh how he was proud that his appetite had shrunk into nothing. It was as if a stone wall had risen up in his digestive system and turned away all thoughts of food. He snacked on one potato chip a day. He drank one bottle of water. And at night, if he was good, he allowed himself a piece of candy, which he immediately hated himself for.

It did not matter that his friends began worrying about him, how shallow his cheeks became, how his moods were erratic, how he wasn’t losing weight but starving weight off of him.

But look at him. He was beautiful—wasn’t he? People loved the new him—didn’t they? Look at him. He had lost fifty pounds in two months. Look at the ladder rungs of his rib cage. Look at the veins that worm through his hands. Look at his face that has become skeletal.

Look. Look. Look.

The story of this boy is chronological because it is a story of his body. It is a story about the changes of his body—inside and outside. Because his body was once fat, and day by day, his body expelled that fat. Time did that. His body recorded time. His body felt it.

But chronology is also important because there comes a moment when the boy finally registers fault. We need that moment of redemption, of change, because when the boy decides what he is doing is detrimental, is a marker of change in his life. And then begins the process of healing, and the process of healing takes time.

Two

Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses : “Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real.”

Seventy-seven

In Bernard Cooper’s essay, “Marketing Memory,” he states that if you want to preserve memory in its purest state, do not write a memoir. Suddenly, your past becomes a book—shaped, contained, revised and revisited language.

Imagine memory as a big messy glob of clay. A writer then begins to work at it. Press and fold. Cut the excess. Give detail to where there was once nothing. We do this for hours, days, years. We live in our heads. And finally, by the end of it all, our messy memory is not a blob of clay. Finally we have something presentable, readable, compressed, conflated.

The detritus of our clay?

We throw it in the trash. We discard it because now there is no use in keeping something that doesn’t serve our narrative.

One Thousand Ten

The ball dropping. The bomb dropping.

I’m sorry I keep coming back to this.

Happy holidays.

Thirteen Point Thirteen

Let’s get right to it. Writing a memoir, writing chronologically, is an unnatural act. David, I agree with you. But the artist makes the unnatural seem natural. The artist, the good artist, creates her art in such a way we do not question veracity. We just live it. We just follow. We say, Take us wherever you please.

Sixty-five

Lidia Yuknavitch, The Chronology of Water: “Events don’t have cause and affect relationships the way you wish they did. It’s all a series of fragments and repetitions and pattern formations. Language and water have this in common…All the events of my life swim in and out between each other. Without chronology. Like in dreams. So if I am thinking of a memory of a relationship, or one about riding a bike, or about my love for literature and art, or when I first touched lips to alcohol, or how much I adored my sister, or the day my father first touched me—there is no linear sense. Language is a metaphor for experience. It’s as arbitrary as the mass of chaotic images we call memory…”

Ten

How does one talk about time when time loses meaning? As person who has gone through depression, I begin to notice, retrospectively, that time has no significance. You are late. You miss meetings. You don’t take the medications you should to get better. You sit in stasis, frozen, a body without a mind, a body without control. You no longer sleep. You no longer eat. Your mind—forever timeless—consumes you, but you spend every moment in this whirlwind of non-linear thoughts.

This is not reserved for the depressed. How about memoirs about abuse, addiction, illness, life-altering accidents, death? How does time affect the narrator? How does time affect the structure of a book? As writers, how can we remain faithful to chronology when our internal chronology is in so much flux?

The answer: we can’t.

I’m not kidding.

As a writer, you are battling two things that prevent this: 1) memory and all its flaws 2) capturing a time in life where time no longer exists.

Einstein said the distinction between the past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion. A memoirist is creating an illusion. This is as post-modern as it gets. The writer of memoir is creating a simulacrum, like reenactments of crimes on Court TV. As Buddha said, “Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present.” And it occurs to me that all memoirs are seen through this lens. Our pasts are filtered through the gaze of the present, and it is this present that begins to sift, sort and build that narrative.

Eighteen

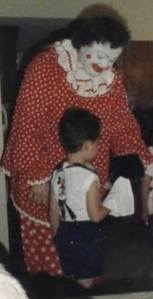

When I was four, I peed on Santa’s lap at Ford City Mall in Chicago. Or was I five? Or three?

I’m forgetting.

But this is not forgotten. I peed on his lap. And he was pissed.

Ten Thousand Eight Hundred Fifty Nine

The writing of a memoir is about not letting go. It is not the western psychological therapy of writing it down to expel thoughts and emotions. It’s just the opposite. It’s about writing it down to understand and live and relive and learn. The writing of a memoir is what Lauren Slater wrote once in an interview: “I, for one, expect my readers to be troubled; I envision my readers as depressed, guilty, or maybe mourning a medication that failed them. I write to say, ‘You are not the only one.’”

One Half

I just asked my mother to end this for me. She asked me what the topic is. I told her time and Christmas and writing.

“Tell them,” she said, “that everyone dies.” Then because she is Buddhist and believes in reincarnation, she added, “But you get to be in line again to do it all over.”

The memoir writer is in line again and again. The memoir writer defies time. She goes back, goes forward, stays still. She relives, recreates, reimagines. It’s a ride, you see, and a memoir writer can’t get sick on it. She has to get in line again and again, before what? Time runs out? Time stops. Time stands still?

Impossible.

Maybe we are all waiting for something to drop.