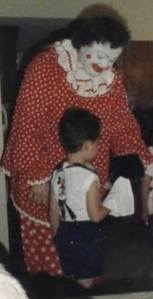

The clown informs the room that he requires a bit of assistance.

“Who here,” he asks grandly, “might assist me in holding a rope?”

I am the one he selects, not because I possess any particularly impressive rope-holding skills, but because the “room” happens to be my living room, and this happens also to be my birthday party.

“Young man,” Chuckles says, “please hold this rope as if your life depends on it.”

In my four-years of life, my life has never depended on anything, though I know I am meant to hold the rope tightly, which I do, gripping either end until my knuckles turn the color of Chuckles’ face paint.

When he questions me further—“Are you sure you’re holding tightly?”—I tell him I think I’m sure.

Moments later, when the rope slips magically from my fingers into his, I feel a lot less sure.

*

Chuckles the Clown died at 6:00a.m. on a Tuesday in the winter of 2004. He was 49-years-old. I was 19 at the time, an oblivious college freshman enrolled in my first creative writing class, anxious to learn how to construct a life in fiction.

At the time of his death, Chuckles and I hadn’t seen each other for 15 years, or so I thought, until my mother revealed that Chuckles had been a member of our church for most of my childhood, that for a few years we likely crossed paths every Sunday.

I remembered him in retrospect—just some curly-haired guy named Charlie who regularly wandered the church foyer following the service. Sometimes he had a cookie in his hand, sometimes a cup of punch.

Without the face paint or the polka-dotted jumpsuit serving as clues, how was I to guess that the man from my church was my clown? Charlie’s greatest trick was keeping his other half hidden, muffling the part of him that seemed to make him whole.

*

In the evenings, after removing the face paint and the jumpsuit, Charlie hunches over his ham radio.

Hello, he calls into the microphone. Is anybody out there?

Nothing but static calls back.

He tweaks the knob a half turn to the left, to the right, then makes a move to adjust the amplifier.

Maybe if I just boost the frequency, he thinks, then maybe someone will hear.

He listens for whispers in the static in the hopes of hearing a voice.

Okay, let’s try this again, folks. Testing 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3. If anybody out there hears my count, go ahead and give me a holler.

Static.

Will somebody give me a holler?

Static.

Please, somebody, give me a holler. I may be in need of assistance.

*

“Let’s give this young man a hand!” Chuckles cries. My partygoers do. I smile modestly, though I am not sure what I have done to deserve their praise. After all, my only task was to hold tight to a rope, though by trick’s end I failed even in doing that.

“A souvenir for my assistant,” Chuckles says, whirring the rope into a knot, “for when you tie the knot.”

He hands it to me.

“Thank you,” I say. “I love it.”

I do not love it.

If it was a balloon animal, perhaps I would love it, but what use do I have for a knot?

*

For years, when the face paint comes off, Charlie spends his evenings shrouded in radio glow.

He tweaks the knobs, then tilts his head sideways as if he himself might serve as the antenna.

Hello again, folks! he calls. Anybody out there feel like shooting the breeze?

The static is all but unbearable now.

Charlie wonders how the world can even hold so much static.

Hello? he retries. Hello hello? Hello Hello Hellooooooo?

He waits, and when that doesn’t work, he’s back to tweaking knobs, twisting them a quarter turn this way, then that way, listening for the moment when the tumblers click into place.

He tries this for an hour, then two, but the tumblers never tumble.

Perhaps it’s a problem with the modulation, he thinks, or the signal, or worst of all, the antenna itself.

Will the repeater repeat my transmission? he wonders. Will the repeater repeat my call for assistance?

Adjustments are made, but the cancer remains an echo in his body.

How’s this? he asks, speaking directly into the microphone. Is this better? Please, someone, tell me if I am better now.

*

At the conclusion of my birthday party, my mother sifts through the wreckage of the wrapping paper in search of Chuckles’ knot. It is nothing to look at—just some knuckle-sized knot pulled tight from a shred of white rope. Certainly it is no balloon animal.

Nevertheless, my mother saves it, placing it into a box on her bedside table where it will sit undisturbed for 20 years. Then, one night, I disturb it—slipping it into my pocket alongside a ring.

That night, when I drop to one knee and ask my girlfriend to marry me, I don’t ask her to marry me exactly.

What I ask is: “Will you tie this knot with me?”

I hold onto one end of the dead clown’s knot and offer her the other.

“Please,” I say. “Tell me you will.”

*

We married—for better or worse, till death do us part—and paid more attention to the knot than the man who tied it. His death did not warrant a national day of mourning. After all, Chuckles wasn’t the most famous clown to die. He wasn’t even the most famous clown named Chuckles to die.

The most famous Chuckles died on October 25, 1975, on an episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show in which another Chuckles the Clown met his tragic/humorous end in a manner ripe for laughter:

Dressed as a peanut, an elephant ate him.

After receiving the news, Mary Tyler Moore watches in horror as her colleagues in the newsroom trade jokes on Chuckles’ unimaginable death.

Newsroom writer Murray Slaughter quips that the tragedy could have been worse: “You know how hard it is to stop after just one peanut!”

Amid the laughter, news director Lou Grant turns to find a mortified Mary watching on.

“We laugh at death,” Lou explains, “because we know that death will have the last laugh on us.”

*

Hello all you listeners out there! Are you out there? This is Chuckles signing off. But before I do, what do you say to one last joke?

Static.

Why did the clown cross the road?

Static.

Anyone?

Static.

To get better reception!

Static, still.

*

When Chuckles needed assistance in the winter of 2004, I was sitting wide-eyed in my first college-level creative writing class.

“What makes a character?” the professor asked. “How do we make a character come alive?”

I’ve lost the notes, but I still remember the gist.

How a character only comes alive once you dream him into being. But sometimes you don’t dream him as much as remember him, modeling your character from some person you used to know.

For example, take a clown you met when you were four and then cement his face with paint. Next, give him a name—Chuckles, for instance, or Charlie—and strive to make that character round. How does one make a character round? For starters, give him a hobby—amateur radio, perhaps—and then flesh him out further by giving him a family and a profession and an obstacle to overcome such as cancer.

No. Scratch that last part. Do not give him cancer. Why would you ever want to give him cancer? Give him some more manageable obstacle, like being eaten by an elephant.

But please, not cancer. Anything but that. It’s hard enough to make your character come alive without giving him a death sentence.

*

What use do I now have for the knot?

None, except to untie it; to take that rope and suture a story as if my life depends on it.

My life does not depend on it. Neither does Charlie’s.

What is life anyway but a joke we tell in an attempt to drone out death?

I don’t need laughter, just a radio receiver that cuts through all the static, something to move me through my feedback loop when all it does is repeat. Because in truth, all I have of Chuckles is a memory that metastasized, leaving me to wonder how many times I’ve relied on feedback rather than relaying the memory properly.

Perhaps what I need more than a receiver is an antenna to help me find the frequency I lost so long ago. Though maybe I never even had that. Maybe what I once heard was the myth of a man I’d constructed in fiction, just some curly-haired guy with a name and a hobby, nothing more.

Listen carefully and I’ll tell you a truth: there are limits to the frequencies we can reach. The human ear—despite its range—remains ill equipped to untangle the static from the echo.