“I believe our best work on earth is in service of likeness. I don’t know what to call it – moments of interpenetration? To feel the exchange across borders.” Lia Purpura “Advice”

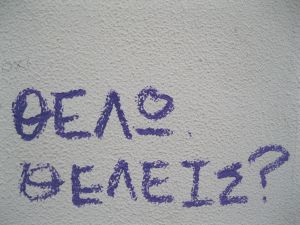

I am not walking to arrive. I am walking with my class in the midst of debt-ravaged Athens. But I am also part of a louder and larger gathering of voices over the walls, scrawled or carefully stenciled: This is some of the language – “Hello/Hell”; “ΘΕΛΟ, ΘΕΛΕΙΣ?” (Ι WANT, YOU WANT?) the English is somehow less elegant.

Language locates us. Maybe this is why Athens is covered in tags, graffiti, continued and continuing conversations over what figuratively and literally are walling in voices that still, fabulously, speak over and across the concrete of so much hell. Hello then. “Hi,” as I say over Skype — another location in time and space. There is something beautifully subversive about this dis-locating capacity of language that re-orients the subject in its mutable subject state. I wonder, for example, how much of a subject anyone (as any one?) can be once taken over, “whelmed” (to use a friend’s phrase) by circumstance. Trauma will do that instantaneously. I think of Paul Celan’s “Death Fugue” the incantatory haunting in the poem’s repetitions:

“Black milk of morning we drink you at night/ we drink you at noontime and dawntime we drink you at dusktime/ we drink and drink/ there’s a man in this house your golden hair Margareta/ your ashen hair Shulamite he cultivates snakes –// “ The repeated, “your golden hair Margareta/ your ashen hair Shulamite -//”[1] which close the poem speak for the haunting as location, the wound also a point of entrance. Purpura’s word, “interpenetration,” an always elsewhere placing. The voices and stencils over the walls of Athens mark already marked intrusions. Any wounding, a violation on an assumption: one keeps walking to find the road again, an intersection where language will orient, give direction: “ΘΕΛΟ, ΘΕΛΕΙΣ?” (Ι WANT, YOU WANT?).

As in Celan, grief’s markings make a sensory haunting of time and space. I traveled to Germany at the beginning of the year where I lived for 3 months, teaching. The landscape was beautiful, the people hospitable, but I carried Athens with me. I find out, too, from Andrew E. Colarusso, poet and editor, that Celan had visited Heidegger in that town. Andrew sends me a section from his essay[2], “Having Walked Beside the Devil: An introduction to Parapoiesis”:

“III. The eros of this space is sublime, so wide as to let in ideas and concepts the size of nations and universes of possibility. Like Paul Celan walking beside Heidegger in relative silence at Todtnauberg, hungry for some affirmation beyond the soft music of the Arnica, Eyebright, the Orchis he was certain to point out for the philosopher. Certainly they spoke on their walk, but it is unclear whether the scion of German poetry, a holocaust survivor, and the bearer of the German intellectual tradition, a passive participant in the horrors of the Third Reich, ever broached the subject of what settled in the historical space between them.

Was Celan’s life ultimately worth the silence he lived with? Had Celan and Heidegger spoken earnestly of the abyss between them, the same dense matter that drew them together, what would one or the other or both have had to sacrifice in order to propel a healing discourse?”

So what might have been the course of their walk if, in Andrew’s imagining, Celan had spoken of that “dense matter” between them: “The eros of this space is sublime, so wide as to let in ideas and concepts the size of nations and universes of possibility.” The intrusions of the walk, also a possibility for healing, the inter-course of a private desire led to unexpected destination? I don’t know what I was expecting in Germany, perhaps a kind of healing from debt-ravaged Athens. I understand the irony.

There was the regular toll of church bells very near where I lived. I bought mushrooms every day from the open market. My consciousness of place, permeated with a January melancholy for as long as January lasted. Unlike travelers of old who stamped their discoveries of place with the language they arrived with (“In the language and attitude of the conquer, Columbus promptly renamed the island he found in the Bahamas San Salvador, claiming it for the king and queen of Spain.”[3]), my arrival dis-placed ways to speak of orientation. The language was foreign, my English inconsequential. I used it to ask for a pretzel with butter in my early mornings until I could make the request in stilted German; the bonds then, when they occurred, occurred in the inter-course or interpenetration of small or larger empathies. Someone suggested I move into a collective when I spoke of financial difficulties. In the collective I learned new recipes and shared Greek ones; we nurtured each other with our different foods as much as with our stories. Lentils, such common fare in Athens, the soup of the poor really, was appreciated as if it were a gourmet offering by my fellow flat mates.

This from Susan Sontag’s “Project for a Trip to China”:

“II

Will this trip appease a longing?

Q. [stalling for time] The longing to go to China, you mean?

A. Any longing.

Archaeology of longings.

But it’s my whole life!”[4]

“Will this trip appease a longing?” I came with vague, indiscriminate desires. For one I was happy to be teaching a small, inspired group of students in the masters program. I also became involved in another cartography of longing; the intersection of a place and time, a personal and literary geography of emotions. “Timing is everything” apparently. It did not matter that I was in another hemisphere, the inter-course would take an altogether different course from what I might have imagined in less dis-located times. I owe something then to the ravages of upheaval and trauma as Andrew suggests in his meditation; it brings new articulations — “Was Celan’s life ultimately worth the silence he lived with?” Andrew asks. Of course it was not all silence. We have the brilliant hauntings in the poetry: “your golden hair Margareta/ your ashen hair Shulamite -//”

I left Germany wishing to take with me all I had gathered there; the images of green, the black forest’s agates and jades. I tried to pack everything. But I forgot things. I left a pair of underwear drying over the heater. I forgot my yoga mat in the overhead baggage compartment on my connecting flight to Athens. Sontag says: “Colonialists collect.” They bring back “Trophies” as in the way Columbus wished to impress the king and queen of Spain, by naming his unknown discovery San Salvador, an island of the Bahamas. But not to blame him too much, man of his times that he was, it’s always tempting to map according to what we want to possess, our traumatized selves re-possessed in some foreign Other. The thing is, there’s no guarantee (in any post-colonial context of the deconstructed subject), that you’ll possess anything close to your assumed desire. Columbus though insisted, to the day he died, that he had discovered a part of India: “Absolutely sure that he had reached the Indies, he called the people los Indios,” (8). Sontag has a grid in her essay “Project for a Trip to China” in which she illustrates “the following Chinese equivalences:” She has five columns titled: EAST, SOUTH, CENTER, WEST, NORTH. The adjectives associated with CENTER are “earth, yellow, end of summer/beginning of autumn/ sympathy” (272). “I would like to be in the center” she says, “The center is earth, yellow…” It includes “Sympathy.”

Sympathy will de-center those ways Columbus constructed his orientation to the world; the self in sympathy is conduit rather than center, a space of interpenetrations. The Greek word for “sympathy” — Συμπάθεια, to sympathize as in to feel for — but Συμπόνια, which is more to the point, is to feel the other’s pain. It is not “The colonialism of soul” in Sontag’s words, but “a border…[where] the soul’s orchestra breaks into a loud fugue. The traveler falters, trembles. Stutters.” (285). It is a strange essay into an “Archeology of longings” — arrival is meant to be a loss of those belongings we started out with, relocation a new intrusion of language: “ΘΕΛΟ, ΘΕΛΕΙΣ?”

[1] Celan, Paul. “Death Fugue” Poets.org. 2000. Accessed May 03, 2014. doi:http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/fugue-death.

[2] http://www.broomestreetreview.blogspot.gr/2014/02/an-abridged-introduction-to-parapoiesis.html

[3] The Heath Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Paul Lauter. Third ed. Vol. 1. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 8. Print.

[4] Sontag, Susan. “Project for a Trip to China” In A Susan Sontag Reader, 268. New York: Penguin, 1983.

Bio: Adrianne Kalfopoulou lives and teaches in Athens Greece. She is the author of two collections of poetry, most recently Passion Maps. RUIN, Essays in Exilic Living, a collection of linked essays, is forthcoming from Red Hen Press September 2014. She is Associate Professor in the Language and Literature Program at Hellenic American University and on the adjunct faculty of the creative writing program at New York University.