I used to say write like everybody you know is dead. It was my signature phrase, a gentle cudgel used to subdue the kind of self-questioning fear that often stunts a writer wading into uncharted waters. An exhortation to write wild, brave and free. Of course this was also when I wrote mostly about the living, when I wrote about the dead primarily as a passing referent, a milepost on my narrative journey. After my grandfather died. Before my grandmother died. When my cat, or aunt, or grade-school choir director was still alive. Mostly I wrote about those who would never read my words. I didn’t worry about my mean-spirited (but true!) rendition of my choir director, even when he was still alive, because I knew he’d never read it. And on those rare occasions when I did write about the dead, I wrote mostly flattering things, gentle odes to those passed on.

But when a longtime friend shows up in your newly-adopted state and drinks himself to death in your presence—a real-life Leaving Las Vegas played out over several weeks—then you will write the dead. The imperative of knowing, of witnessing—whether it be for atonement, or to honor, or to punish—you will write the dead. I am still writing the dead, although the story has trickled out on me at ninety pages—too short for a book, too long for an essay. An Essayvella?

*

Last summer I started writing by hand again, scrawling away in a gray composition notebook. Perched on the balcony of our carriage house apartment, surrounded by my potted palms and tropical plants, I let the summer breeze lull me into believing that I was playing the part of Hemingway in Key West, rather than Appalachian Ohio.

I hadn’t written with any serious intent in a notebook for six years, having finally trained myself during my MFA program to “be creative” on my laptop. I had been cursed with a stubborn certainty from the earliest years of my literary dabbling: a certainty that one could not—or at least I could not—type creatively in the same manner as I scrawled my barely-legible notebook odysseys. But after a decade of writing longhand, and then turning around and typing those words into a Word document, my wrists were perpetually sore, and my forearms plagued by a recurrent tingling numbness. Fear of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, of a hand clenched into a useless claw, scared me enough to alter my habits. So I pushed on past my ingrained superstition and discovered that in fact I could conjure expression from the percussion of my fingers on the keys. And every muscle and nerve from my knuckles to my shoulder blades thanked me.

Part of my decision to return to writing longhand was about trying to rediscover the joy of writing I used to know before I was a “Writer.” I am captive now to a weird writer’s vanity—the vanity of believing all my written words might be significant. It’s an absurd idea. I still generate far more future trash than I do marketable prose. But I no longer feel good “free-doodling.” Writing has become a commodity, or more accurately the time I have for writing is a commodity, and thus I feel the pressure to make that time count. Each word part of a sentence, part of a paragraph, part of a final essay to be submitted, part of a book of said essays to be offered up as sacrifice to the capricious gods of publishing. By getting “serious” about writing, I robbed the act of fun.

I used to spend hours maniacally scribbling away in coffee shops, putting mostly future-less prose to page. Sure I was going to be a writer someday. But I wasn’t there yet, and my 90s daydreams of writer greatness were barely more realistic than my previously imagined futures as a rock star or NBA power forward. Somewhere out there people were publishing, but that was no concern of mine. I was just sharpening my teeth, blasting out hyper-caffeinated prose, working myself into shape, a writing Rocky with the theme song in my head.

Then one day you publish something. Then you get into an MFA program. Publish a few more things. Become Nonfiction Editor for a lit journal. Go to some conferences. Get into a PhD program. Compile a big enough Word document to have a book or two or three. And where once I merrily dashed off reams of sketches without intent, now I agonize over all the work—the finished pieces still searching for homes, all my megabytes of stalled stories, embers of essay. Now I cringe when the word-flow dams up, when the “essayer” fails to bear fruit. Now I feel the pressure to produce. Now that I have stepped into the ring I have to confront, each time I write, the fear that it might not happen, that nobody is guaranteed a book contract just for finishing their work, that I might peak with a few good essays and then fade away…

*

I wrote the dead swamped in grief. I wrote in regret. I wrote in anger. Lambasted myself on the page for being unable to save my alcoholic friend. Lambasted him on the page for being unwilling to save himself. I wrote in forgiveness. I wrote in love. I wrote in remembrance. As the years scrolled by and the death receded back in the rear-view mirror I wrote with increasing detachment, when I wrote him at all. The tidal wave of early words slowed to a river, then a stream, then a trickle. I had said all I could say, disgorged my pages and turned instead to dabbling with rearrangements, trying to make the puzzle pieces fit into some semblance of a whole. I missed his April birthday this year, for the first time since his death. Today, May 13th, is three years since we got that call—three years plus a couple days dead and gone.

*

The past is malleable; we shape it and polish it until it resembles what is most palatable to our current selves, and our reflection of those previous incarnations. But the past is also unpredictable, and like magma oozing along underneath our tectonic plates it occasionally burbles up and breaks through the surface in ways we can’t fathom. Early October, the mid-George W. Bush years, waiting for a train at the Milan airport. It had been six years since that summer in Holland, my brief interlude as romantic expat abroad, and yet waiting for the train I could feel the swell of nostalgia and sorrow bursting up from a long-dormant core, spurred by the simple fact that it was the first time I’d been back in Europe since those events. Melancholy seeping from my pores like magma, and a visceral certainty that I could punch through the wall of the tunnel to find that other me, that other past lurking in shadows just outside the corner of my vision.

*

I think part of the allure of blogging is not just the immediacy of your words, the timeliness in response to current events, but also the immediacy of the self. This is who I am, right now. This is my life, my ideas, my brain on the page at this moment, date-stamped for perpetuity. This is the real-time wine and wafer; eat and drink and be one with me.

Because even in the quickest publication turnarounds there is normally a lag-time of months or sometimes years between those words you wrote at that moment when they were fully you, and the day those words go public. By the time my words see the light of day I am often tired of them, having rolled the Sisyphean literary boulder up the hill, writing, shaping, re-shaping. And then you see those words from this lag-time, where they are always that younger you, always a slightly different version, so that in reading yourself at the moment of publication you are reading your own history.

Some of my oldest Word documents pre-date the Millennium. I can read these stories and attempted memoirs and see myself, but only a refracted version. In a sense I reclaim my history every time I reread them, which is why it is simultaneously exhilarating and frightening to read those old pieces—or to delve into my old journals, which date back nearly a quarter-century. In the intervening decades those memories were sanded down and sun-bleached, but then I will re-read that passage from the journal of an angst-ridden 19-year-old and be viscerally reminded of who I was then, of that younger, smaller me that still exists in this older form, still forms the inner rings of the tree of me. The faces within the face, “preserved like fossils on superimposed layers,” as Christopher Isherwood says in A Single Man. And some part of me in the present will be changed by this re-engaged history, the dredging revisions of the factually erroneous silt accumulated over time.

*

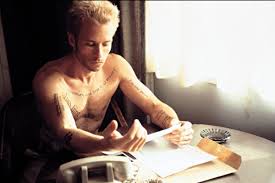

Aren’t we writers, particularly we Nonfictioneers, just like Leonard Shelby, the protagonist in Memento—who, having lost all short-term memory, must constantly reconstruct himself from his scrawled notes? Those important truths tattooed all over his torso, never to be forgotten. Aren’t we writers tattooing ourselves every time we publish?

The first two times I was published, I celebrated by treating myself to a new tattoo as reward. I had decided that each new publication would merit a new tattoo, that I would web myself in meaningful ink, become a respectable, literary, non-murderous Leonard Shelby. But I haven’t kept up that tradition. I meant to, but as subsequent publications happened I realized that they were not all of equal significance, and probably not all worthy of their own ink. And I had other things to spend money on, other people to consider. Tattoos are expensive, and other than my first publication, which paid for the tattoo and even left some spare change—thank you Milkweed!—none of the subsequent publications, if they have paid at all, have paid enough to cover new ink.

*

I have moved on, for the moment, to writing the living. Writing a book about my biological father, or more accurately about our relationship, and what it meant to grow up with a gay father in the 1980s during the height of the AIDS crisis. This is a story I’ve always known I had to tell, one that friends and professors alike have chided me for delaying. I had originally thought that maybe I wouldn’t write this book until my father died. That maybe out of respect for him, I ought to wait. But I realized something important, in the process of writing the book of the dead friend: it isn’t easier when they’re gone. In many ways it’s harder. What you might think of as the advantage of avoiding those awkward moments—they’ll never read it—are offset by the guilt one feels for writing them without the possibility of correction. Of being able to say anything you want. Of presenting their likeness without consent.

Part of me fears certain passages I’ve written already about my father, things that will surely hurt him to read. Part of me also fears the passages I haven’t written yet, the stories I’m slowly working myself up to, the ones I can’t imagine having a conversation with my father about. But we can do that. We can talk. And maybe in talking about these events, the stories themselves will become better, truer—more purely Nonfiction—as we hash out the differences in our memories to find a palatable shared truth. Isn’t that much more likely to be true than my singular version of events? Isn’t that more fair, more honest?

*

Those old Microsoft Word documents are in danger of becoming outdated, of living past the current technology’s ability to reach back and speak to them. It’s weird to think about because we always assume that technological improvements are without consequence, inherently positive. But of course with each passing year the incentive diminishes for the engineers at Microsoft to make sure that the newest version of Word is still configured to be compatible with antique, pre-Millennium versions of itself. And I keep ignoring the compatibility messages when I open one of these ancient scrolls, confident in the fact that we no longer live in the dark ages of technology when Apple and Microsoft spoke separate languages, warring across a tech channel like the French and the British. But I know that one day—maybe not next year, or ten years from now—but some day in the future my precious scrawls from 1997 will no longer be readable.

Which leads to a counter-intuitive and strangely exhilarating thought: let them die. Delete all. Delete them all. Like John Steinbeck burning The Oklahomans—his first attempt at The Grapes of Wrath—and starting over from scratch. Imagine the weightlessness of returning to a blank slate. Of digitally burning everything not already in print. Of saying thanks for all the practice, now toss those canvasses into the bonfire and begin anew. What if we could start over? What if we could erase everything we’d ever written, and truly forget? What would my next sentence be if I knew I would never re-read my old words?

Kirk Wisland’s work has appeared in The Normal School, Creative Nonfiction, The Diagram, Paper Darts, Electric Literature, Phoebe, Essay Daily, and the Milkweed Press Anthology Fiction on a Stick. He is a doctoral student in Creative Writing at Ohio University. He has not yet hit “delete all.”

Reblogged this on courtneyambers.